Sometimes I like to think of humanity as a big engine for converting energy into happiness. I don’t want to fuss too much over what “happiness” means here. It is the thing I think we generally seek in our lives. I wrote a whole book about beatitude if you want to get into that.

But whatever else happiness is, from a scientific point of view, I think it has to be energy. A fit of laughter or dance of joy is kinetic energy in the body. Contemplation of a beautiful building is electrochemical energy in the optic nerves and the brain. Love feels like a type of warmth and passion like a type of heat, and at some level probably they are.

Pure pleasures of the soul are a different story, perhaps. But I am talking about happiness in this world, and that is generally embodied. And embodied happiness, it seems to me, is always energy of some sort.

And so the meaning of life is an energy conversion: from forms of energy that are not happiness to forms of energy that are.

The Sun is our primary source of energy. Archaic societies generally converted this into happiness by eating the stored energy in plants and animals, and then living: playing, talking, having sex, praying–whatever they did to realise happiness.

Today we harness the energy stored in fossilised carbon. This has turned out to be a tragedy, but there is something beautiful about it. Fossil fuels power human life, and human life is a wonderful thing. Petrol-burning cars and kerosene-burning airplanes carry families to spend time with distant loved-ones. Coal-generated electricity powers portable computers, allowing billions of people to play games, share jokes, and learn about the world. Burning natural gas keeps children warm, electric refrigeration preserves their food and medicine, and, as a result, children tend to survive past infancy in rich countries, sparing the majority of parents there a type of anguish that, unimaginable to them, is par for the course in poorer places and earlier ages.

The energy for all this was stored by plants and animals millions of years ago. Perhaps they expended it in pursuit of their own kinds of happiness. Now it is resurrected to again enter the cosmic dance of life. I don’t think we should forget the magic of this, even as we realise our great mistake in harnessing the power of fossil fuels to the extent that we have.

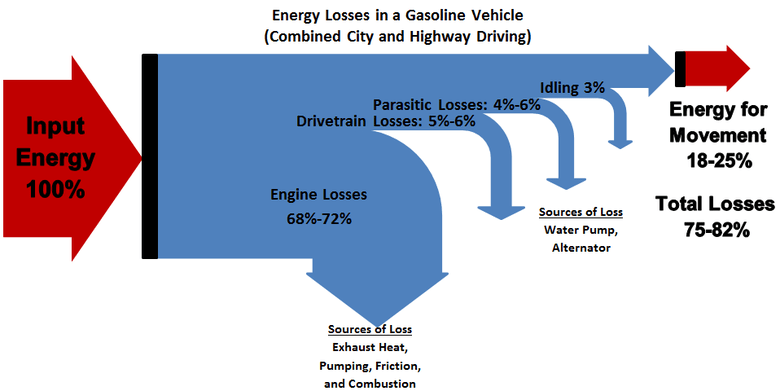

Any deliberate conversion of energy is inefficient. Some energy will be “lost”, which means converted to an unwanted form of energy. Usually the lost energy is heat. Over half of the energy of an internal combustion engine goes into heating the surrounding air, which wasn’t the point. The same goes for a whirring turbine in a power station, though to a lesser extent.

Since an inefficient energy-converter is one that generates a lot of pointless heat, I propose that we use the term “hedonic heat” for energy we waste in our attempt to produce happiness.

There are lots of kinds of hedonic heat.

There is, for example, the interfering kind. The industrial revolution gave us access to an unimaginably vast underground reservoir of energy, which we used to create comfortable, healthy, entertaining lives. But the process of extracting it creates a lot of unhappiness for the industrial proletariat. Creating unhappiness in the pursuit of happiness is a sort of self-interference in the happiness engine. It goes in the wrong direction, just as the piston of a combustion engine, in order to go the “right” way in the power stroke, also has to go the wrong way half of the time.

Another form of interfering hedonic heat is climate change. Fossil fuels are used to power human life, but some of the energy is powering processes to change the Earth’s climate. That is not at all the intention. It is already creating a lot of unhappiness, and there is much more to come. I don’t think that humans are on the whole stupid or evil. It is just very difficult to build an efficient hedonic converter, and sometimes we think we have succeeded much more than we actually have.

Then there is conscious waste. Synthetic ammonia production and mechanised farming allowed for the conversion of chemical energy into food on an unprecedented scale, allowing billions of human lives to take place that would otherwise not have taken place. I hope that many of those able to live as a direct result of these miraculous inventions used their lives to create happiness. But of course many of them also spent time doing things that made them and others unhappy.

Finally, there is unconscious waste. Again, much of the energy from fossil fuels goes into pointlessly heating up the air around engines and turbines. You might say that a consequence of synthetic ammonia is that food production is now so easy that we become complacent about wasting it–not just in the home, but through the whole supply chain. For example, food distribution centres often have no refrigeration facilities. Easy to fix, but even easier to be lazy in a world of abundance.

Another form of unconscious waste is more difficult to identify. A diagram from Vaclav Smil’s Energy and Civilization: A History (ch.6), plots per-capita energy use against the UN’s Human Development Index for various countries:

Obviously the Human Development Index is at best an extremely crude measure of human happiness. Still, it seems striking that the USA, for example, consumes nearly three times as much energy as it needs to attain its level.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the USA is a highly inefficient hedonic engine. 100 GJ of energy per year seems like plenty to live a very happy life, if other things go well for you. If they go badly, more energy is unlikely to help. Medical technology that saves lives or dramatically improves quality of life requires energy, of course, but not on this scale: a full life-support machine, I have heard, takes about 7 GJ per year.

So where does all the superfluous energy go? Adam Smith once asked: “to what purpose is all the toil and bustle of this world? what is the end of avarice and ambition, of the pursuit of wealth, of power, and preheminence?” (Theory of Moral Sentiments, Part 2, Chapter 2). “Is it”, he asked, “to supply the necessities of nature?” No! “The wages of the meanest labourer can supply them.” Indeed, Smith believed (perhaps somewhat naively) that the “meanest labourer” is able to live relatively comfortably, even managing to buy “conveniences, which may be regarded as superfluities”. Why do people aspire to more?

Do they imagine that their stomach is better or their sleep sounder in a palace than in a cottage? The contrary has been so often observed, and, indeed, is so very obvious, though it had never been observed, that there is no body ignorant of it.

Finally, Smith gives his explanation:

From whence, then, arises that emulation which runs through all the different ranks of men, and what are the advantages which we propose by that great purpose of human life which we call bettering our condition? To be observed, to be attended to, to be taken notice of with sympathy, complacency and approbation, are all the advantages which we can propose to derive from it. It is the vanity, not the ease, or the pleasure, which interests us.

But pursuing vanity leads to great inefficiency. If your aim is “to be observed, to be attended to”, then you are already in a race to the bottom with the others sharing that goal. If the Joneses on your street buy a luxury car, then you, to keep being noticed, must buy a better one. If they buy a big, shiny SUV, then you must buy a bigger, shinier one. If they buy two, then you’d better buy three. Before you know it, you and the Joneses are consuming thousands of GJ of energy per year just to stay level with each other, which is precisely where you were when you were consuming only hundreds.

All the extra energy went into creating something other than happiness–shareholder value for the car companies, perhaps, but then what do they do with that wealth besides get into other arms races of just the same sort?

For me at least, this is one of the most frustrating sorts of hedonic heat generated by our human engine. Worse still, fixing it requires better philosophy rather than better engineering.