The word “neoliberalism” is thrown around in many leftist circles. In many centrist circles it is complained about as an empty term. To me it has a meaning, although others will disagree with my definition.

A liberal, as far as political economy goes, believes in letting free markets determine social outcomes with minimal intervention from the state. A neoliberal believes in using the power of the state to force the social outcome that a free market, if only such a thing were possible, would have delivered. Neoliberalism is coercion trying to simulate freedom, on some definition of “freedom”.

What are its consequences?

Labour List posted a draft of an election manifesto for the UK Labour Party, which promises several important actions on climate change, such as delivering clean electricity by 2030 and doubling capacity for offshore wind generation, tripling capacity for solar generation, and quadrupling onshore wind generation (as has become typical, the focus is entirely on generation and transmission is not mentioned).

But above these is the commitment: “Invest £28bn of public capital a year into the green economy, alongside an active industrial strategy, with strategic public investment attracting private sector investment.”

The book Economic Planning in an Age of Climate Crisis estimates that the total investment required to decarbonise energy in the UK is in the range of £300bn to £1748bn, with a midpoint of around £1000bn. Reaching the target by 2030 would mean spending on the order of at least £33bn per year, but more likely upwards of £100bn (you’ll find comparable figures in Earth for All, but presented with better PR as a mere 2-4% of GDP). The authors of Economic Planning conclude that: “There is essentially no chance that free-market economics can achieve this”. At any rate, Labour’s promised £28bn, let alone what it could actually get through Parliament, won’t cut it.

There is also the hope of “attracting private sector investment”. But now we have to think about the neoliberal institutions standing in the way, especially the Bank of England. Even the promised £28bn of public investment would, other things equal, drive inflation. In response, the BoE would raise the interest rate. This would curtail the capacity of everyone to borrow, including any private investors in a green transition and public institutions trying to spend on climate mitigation.

If the BoE were willing to raise borrowing costs for the fossil fuel sector and not for the green sector, that could accelerate the green transition. But the BoE is not willing, since this would violate “central bank neutrality”. On the neoliberal consensus, the job of the central bank is not to plan the economy; it is only to control the volume of overall credit and the price level. The central bank is supposed to be “neutral” with respect to the “market” outcome, controlling only aggregate volumes. And the fact that central bankers are appointed, not elected–a centrepiece of the neoliberal setup–means that central banks can’t get involved in economic planning or policy without severely violating democratic norms.

But central bank neutrality is not a liberal policy. It’s not that central banks leave the markets to themselves. They are up to the eyeballs in the markets, constantly buying assets from the banks, which the banks create by lending into different parts of the economy.

In practice central banks don’t behave in a politically neutral way (see here and here). Their collateral frameworks are effectively an economic planning instrument, as Kjell Nyborg nicely outlines. Neutrality doesn’t mean that they don’t plan the economy. It means that they don’t plan it for any identifiable social purpose besides the “neutral” one of having capitalists get richer.

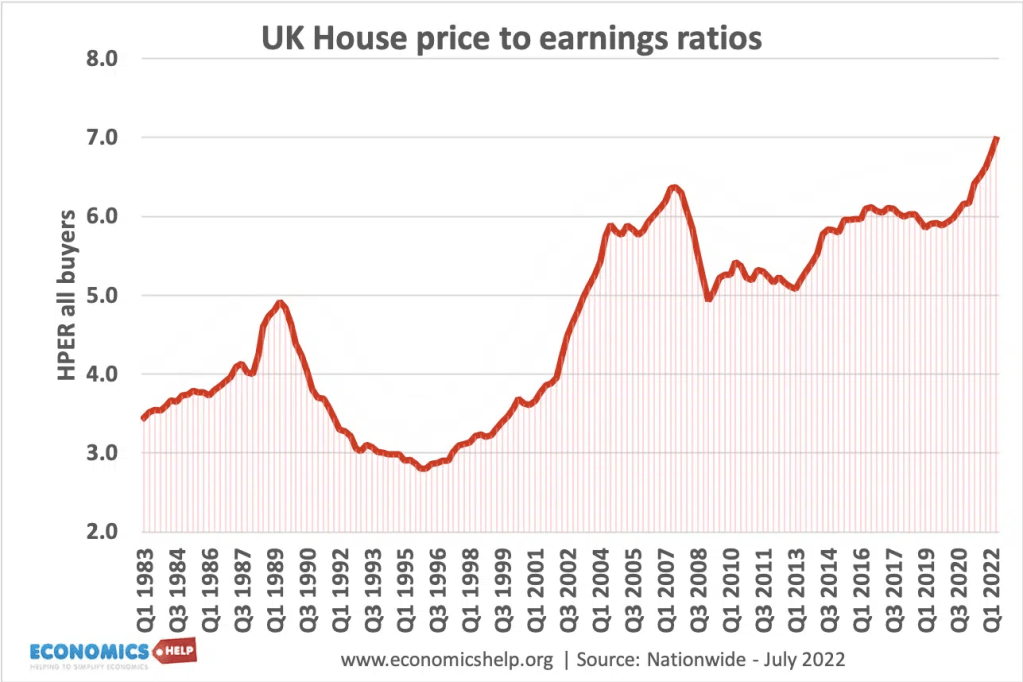

To give one illustrative example. The BoE agrees to accept mortgages (in bulk: “mortgage-backed-securities”) as collateral from banks for loans of reserves–effectively paying cash to buy mortgages from the banks. Thus the banks are motivated to lend out lots of mortgages. There’s no risk in making a loan that you can immediately take to Cash Converters, I mean the Bank of England. The BoE doesn’t collateralise loans for house building at an equivalent level (look what happens to local councils when they try to borrow for this). Thus you have a policy of loose money for house-buying and tight money for house-building, in other words pushing on demand and pulling on supply, in other words a machine for inflating prices. And so:

Hardly a neutral policy.

There are many other examples of non-neutrality. For example, central banks typically collateralise listed corporate bonds, thus incentivising banks to lend to big corporations (who issue listed bonds) and not small businesses (who don’t).

Central banking is a neoliberal institution by my definition since it uses the coercive power of its state backing to bring about a certain image of what a free market would deliver: a world in which wealthy asset holders get wealthier and big business has a leg up over small business. That might be just what a free market would deliver, but the fact is that it’s not a free market delivering it. What is realised is the vision that a policy team within a central bank has of what the market should deliver. While cynicism is an ugly tendency, we shouldn’t be altogether surprised that they tend to think the market should deliver wealth for people like themselves.

So long as the BoE remains “neutral” there isn’t much hope of getting required climate investment going. “Neutral” policy favours big, established businesses with listed assets over small new entrants, which in practice means fossil fuels get cheap bank money and green tech goes to vulture/venture capital. “Neutral” policy also means raising the rate in response to new public investment, meaning a big shocking increase in the public debt and political death for the investment.

One way to get to net zero would be Zero Rate for Zero Emissions. Take over the BoE and make it set the rate permanently at zero. To maintain the rate is easy: the BoE would just give banks an unlimited, unsecured overdraft at 0% (or a low rate to compensate for inflation). To retain their access to this overdraft, banks would have to lend only for approved ventures, submitting their balance sheets for regular review (off-balance-sheet stuff could be banned in general). Approval could be granted by the elected government, by randomly chosen mini-publics advised by scientific and industry experts, etc.

The approving body would be tasked with directing investment towards decarbonisation and away from fossil fuels as well as supporting other social goals, rather than only the “neutral” goal of advancing capitalist interests.

With the interest rate at 0%, the state could invest as much as it needed without worrying about exploding debt (if you borrow at 0% you only need to average a tiny amount of growth for the debt to dissolve over time). To protect against abuse of this power by elected officials, an appointed fiscal council could monitor the budget. Again, this fiscal council could be a “mini public” and would measure broad social costs and benefits rather than being imprisoned within the “neutral” policy of ensuring that wealth compounds.

That’s what non-neoliberalism would look like, I think, in the nearest possible world. Joan Robinson stated that the meaning of a proposition is what it denies. So now we have a meaning for “neoliberalism”. And it turns out that the New Left Review types are basically right, though their language is sometimes too waffly to be sure. Neoliberalism locks in severe climate change. Neoliberalism hamstrings public investment. It gives holders of listed assets vastly disproportionate access to capital, rigging the system in favour of established wealth. It doesn’t just enshrine the status quo, it takes the status quo to the nth degree.

Neoliberalism is the problem.